|

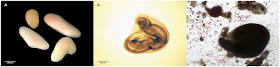

| (a) Opened European eel swim bladder showing adult Anguillicola crassus, (b) round goby from the stomach of an eel. Photos from Figure 1 of Emde et al. (2014) |

Anguillicola crassus is a nematode parasite from Japan, introduced to Europe with Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica), their original definitive host. It first infects invertebrates, such as copepods, where it grows to its third larval stage. It can then go on to parasitize several different fish species, which become infected when they ingest the parasitized copepod (this is what’s known as “trophic transmission”). Some of these fish only transport the worm, while others may act as alternative final hosts. Typically, the parasite finally reaches the eel after this final host eats a parasitized fish or crustacean.

The introduction of this invasive nematode species to Europe has had a devastating effect on the overall European eel (Anguilla anguilla) stock leading to a massive decline, and the species becoming classified as critically endangered. The European eel life-cycle is very peculiar: they individually undergo a 5000 km spawning migration from European coasts to the Sargasso Sea at depths fluctuating between 200 and 1000 meters. Anguillicola crassus impacts their survival by infecting their swim bladder and reducing their swimming performance, and possibly leading to the host’s death during their migration journey.

But some fish species have developed an immune response that can cause the nematode’s death. Nonetheless, in the Rhine river, recent studies revealed that invasive A. crassus found an intriguing way to avoid the immune defence of the round goby Neogobius melanostomus by using another European invasive parasite: Pomphorhynchus laevis. This acanthocephalan worm originally invaded the Rhine river from the Ponto-Caspian region using the Danube canal by hiding in the body of its round goby host.

So how does A. crassus employ a “Trojan horse” strategy to avoid detection by the round goby? When the acanthocephalan infects the round goby, the worm turns into a cocoon-like cyst, and even though the acanthocephalan parasite is encapsulated by the goby’s immune response, its infective power remains. What is even more interesting about this cyst formation is the high intensity of A. crassus nematode larvae within P. laevis cysts in the round goby. Here you have a well packaged trio of non-native European species. This evasion strategy is used by A. crassus to avoid the goby’s immune response and turns the round goby into an unusual second intermediate host due to the distinct geographic origin of the nematode A. crassus, the round goby, and the acanthocephalan, P. laevis.

The cunning nematode uses the cysts as “Trojan horses” facilitating its establishment in the host, like the Greeks in Troy. The relationship between both parasites can be defined as “facultative hyperparasitism” where the cyst gives protection to the nematode, while the acanthocephalan worm continues to develop as normal. This strategy comes to be a considerable problem since it increases the chances of A. crassus infecting European eels as they remain infectious after consumption by the round goby and excystation of the acanthocephalan, along with its nematode passenger. And we know the damaging effects it causes on eel populations, in fact A. crassus has been recognised as one of the 100 “worst” exotic European species because of its impact on the European eel.

This case highlights not only the complexity of the parasite life-cycles involved and the impact of multiple human-driven invasions by invasive species, but also the large impact they can have on native species when combined.

References:

Hohenadler, M.A.A., Honka, K.I., Emde, S. et al. (2018). First evidence for a possible invasional meltdown among invasive fish parasites. Scientific Reports 8, 15085.

Emde, S., Rueckert, S., Kochmann, J., Knopf, K., Sures, B., & Klimpel, S. (2014). Nematode eel parasite found inside acanthocephalan cysts—“Trojan horse” strategy?. Parasites and Vectors, 7, 504.

post written by Juliette Villechanoux