Pearls may look beautiful to us, but for some parasites, they represent a slow and claustrophobic death. Pearls are secreted by the soft and fleshy mantle, the part of a mollusc's body that also produces the shell. Indeed, pearls and shells are made from the same material - calcium carbonate. For the shellfish that produce them, pearls are battle scars of their fight against parasites.

|

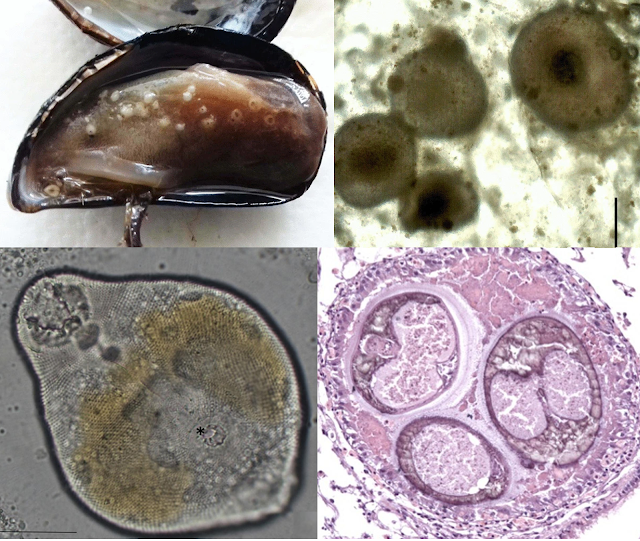

| Top left: Mussel infected with Parvatrema, Top right: Pearls from a mussel Bottom left: Parvatrema metacercaria stage from a mussel, Bottom right: Cross-section of a pearl showing three flukes trapped within. Top row of photos from Fig 1 of this paper. Bottom row of photos from Fig. 2 of the paper. |

Bivalves are host to a wide range of different parasites that use them as a home, a site of propagation, or even as a convenient vehicle to their next host. One of the most common types of parasites that infect bivalves are trematode flukes. Some species embed themselves stubbornly in the mollsuc's tissue, others impair their ability to use parts of their body, and there are even some that end up castrating their shellfish host. Sometimes, these seemingly passive molluscs put up a fight against these tiny intruders, especially when they get into the mantle fold. And they do so by secreting calcium carbonate around the invading parasite, smothering these flukes alive - and the result of that gruesome interaction is a pearl.

The study being featured in this post looked at the frequency of pearls and parasites in mussels on the northwestern Adriatic coast. The flukes that are most commonly associated with pearls there are those from the Gymnophallidae family, and this study focus on one particular genus - Parvatrema. These flukes use mussels as their intermediate host, where the larvae temporarily reside and develop until they are eaten by shorebirds - this parasite's final host.

Out of the 158 mussels that the researchers examined, about two-thirds of them were infected, and most of the mussels had a mix of both live flukes and pearls.Their parasite load varied quite a lot, from some mussels with a few flukes, to one with over 3700 flukes. But on average, each mussel harboured about 200 flukes. The flukes were scattered throughout the mussel's body, but most were concentrated near the gonads, and some were found at the base of the gills. A few were squeezed in between the mantle and the shell - and it is those that are at the most risk of being turned into pearls.

Speaking of which, about half the mussels that the researchers examined had pearls of some sort in them. But there were far fewer pearls than there were flukes. Each mussel had 35 pearls on average, but they were nowhere near the size of pearls most people associate with jewellery. These pearls were about the same size as fine sand grains, but they were pearls nevertheless - complete with entombed fluke(s) in each of them.

The high prevalence of Parvatrema in mussels from this area means that it could be risky to set up mussel farms there, at least near the coast where the parasite's bird hosts like to hang out. No one wants to buy mussels riddled with parasites, and while pearls are considered as valuable, the type of pearls found in these mussels only decrease their market value. That is one of the reasons why some mussel farming operation are located offshore where they won't be exposed to Parvatrema and other parasitic flukes.

Based on the results of the study, pearl formation seems a bit hit-or-miss as a defensive mechanism. The majority of flukes get away with living rent-free in the mussels without setting off the pearly deathtraps, and it's not entirely clear why some of them trigger pearl formation, while most flukes are left alone. Despite this, some recent studies indicate that bivalves are not the only molluscs that can entomb their parasites that way. Some land snails are also capable of sealing away various parasites such as flukes and roundworms into their shell.

So it seems the molluscs have evolved a general two-in-one defensive package that can potentially protect them against both predators and parasites. While neither shell nor pearls offer guaranteed protection against predators and parasites respectively, it's still better than having nothing at all.

Reference:

Marchiori, E., Quaglio, F., Franzo, G., Brocca, G., Aleksi, S., Cerchier, P., Cassini, R. & Marcer, F. (2023). Pearl formation associated with gymnophallid metacercariae in Mytilus galloprovincialis from the Northwestern Adriatic coast: Preliminary observations. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 196: 107854.

No comments:

Post a Comment