In the cold rivers and lakes of the arctic and subarctic region, there live some rather peculiar worms with a face full of tiny hooks and an appetite for blood. These worms live as ectoparasites of fish, and they belong to a group called Acanthobdellida - relatives of leeches that seem to have gone down their own evolutionary path. These worms have also been called "hook-faced fish worms" and the entire group consists of only two known species - Acanthobdella peledina and Paracanthobdella livanowi.

|

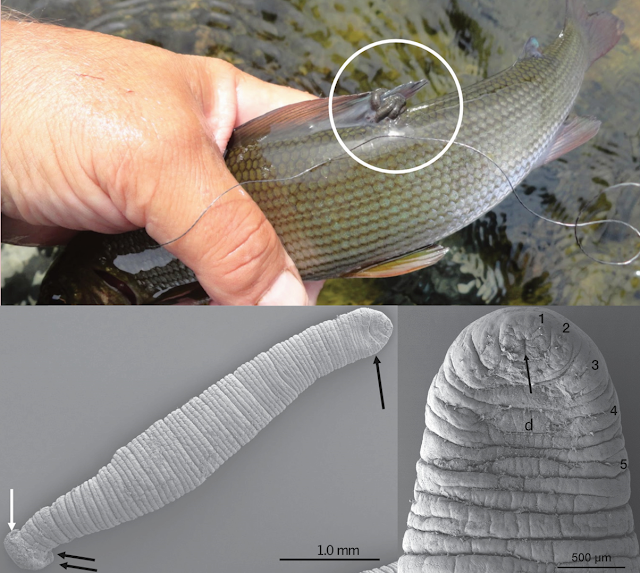

| Top: Acanthobdella peledina on a grayling. Bottom: Scanning electron micrograph of the whole worm (left) and close-up of the anterior body region (right). Photos from Figure 1, 6, and 7 of the paper |

Their mouthpart has been described as being a less sophisticated version of a leech's mouthpart - they lack the saw-edged jaws or the extensible proboscis found in many leeches, nor do they have the muscular sucker which surrounds the mouth. Instead, they have a protrusible pharynx and a series of hooks on the first five segments of the body, which they use to attach themselves to their fishy hosts.

They have previously been considered to be a "missing link" between leeches and the rest of the Clitellata - the group of segmented worms that also includes earthworms and tubifex worms - as they have certain features which are commonly found in other clitellate worms but are absent in leeches. This includes having tiny bristles (called chaeta) on their segments, and a reproductive system similar to those found in earthworms.

Acanthobdella peledina is found all across the subarctic, where they range from being relatively rare to being found on over two-thirds of the fish at a given location. Given it is so widely distributed, with populations scattered across different geographical locales, could each of those distinct populations actually be different species? A group of researchers set out to determine whether there are actually more species of these hook-faced worms than meets the eye. Furthermore, they also wanted to find out how closely related Acanthobdella and Paracanthobdella are to each other. They did so by comparing museum specimens of hook-faced worms which have been collected from sites across the subarctic, including Norway, Sweden, Finland, Alaska, and Russia.

Aside from examining their anatomical features, the researchers also compared five different key marker genes from these worms. Some of those DNA segments came from the mitochondria, others from the cell's nucleus. The reason for comparing multiple genes is that each has their own histories, and may offer different perspectives on the organism's evolutionary history. It is like interviewing different witnesses at a crime scene. Unfortunately, for whatever reasons, the DNA of these worms proved to be particularly challenging to amplify and sequence, so for most specimens they were only able to sequence up to four of the five genetic markers they were aiming for, with some specimens only yielding sequences for two of the genes. Despite that limitation, the researchers were able to use the sequences they obtained to resolve the hook-faced worm's evolutionary history.

Despite their wide distribution across the arctic and subarctic regions, Acanthobdella peledina does appear to be a single, widespread species. While the Alaskan population of worms are genetically distinct from the Nordic population, they are not dissimilar enough for them to be considered as separate species. Furthermore, based on their analysis, the two living species of hook-faced worms are quite closely related to each other. In fact, it seems they had only diverged from each other just prior to the last ice age. So, far from being some kind of "missing link" between leeches and other clitellate worms, these hook-faced worms belong to their own distinct group.

But while the two living species had shared a common history until relatively recently, the hook-faced worms as a group had evolutionarily split off from the leeches a long time ago. Based on available data on these worms, this might have occurred during the early Cenozoic as the ancestors of the hook-faced worms became specialised on arctic freshwater fishes that arose during that era, such as salmonids.

So it might have been the pursuit of salmonids that had sent these worms down their own distinct path - a story which is probably relatable to any fly fishers out there.

Reference:

de Carle, D. B., Gajda, Ł., Bielecki, A., Cios, S., Cichocka, J. M., Golden, H. E., Gryska, A. D., Sokolov, S., Shedko, M. B., Knudsen, R., Utevsky, S., Świątek, P. & Tessler, M. (2022). Recent evolution of ancient Arctic leech relatives: systematics of Acanthobdellida. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 196: 149-168.