Horsehair worms are a menace to crickets (as well as mantis, millipedes, and centipedes) everywhere. Imagine being a cricket going about your day when you happen upon a protein-rich snack in the form of a smaller invertebrate. As you munch on this treat, you have also unknowingly ingested a parasitic larva. Over the course of the next few months, this parasite will grow so large that it fills up your entire abdomen, displacing all your internal organs. And when it comes slithering out of your belly, it is several times the length of your body. Life can be rough for crickets.

|

| Left: Free-living adults Gordius wulingensis in shallow water pool, Top Right: Cave cricket with multiple emerging worms, Bottom Right: Adult worm among rocks. Photos from Figure 7 of the paper |

Hairworms are mostly associated with aquatic environments such as streams and rivers, though there are also some species which are found among wet soil. If you are observant (and lucky), you may spot adult hairworms crawling or swimming out in the open. But the hairworm featured in this post is found in near total darkness, sheltered in limestone caves where it parasitises the caves' inhabitants.

Gordius wulingensis is a species of hairworm which can be found in karstic caves throughout the Hunan province in China. It was first discovered in 2014 at Jinji cave (金鸡洞) in Yongshun county, but before it could be properly described, those initial specimens were lost, and it wasn't until 2019 that the worm was rediscovered, and researchers began searching more extensively for this hairworm across Hunan province. The worms described in this particular study were collected from caves at the Wuling Mountains.

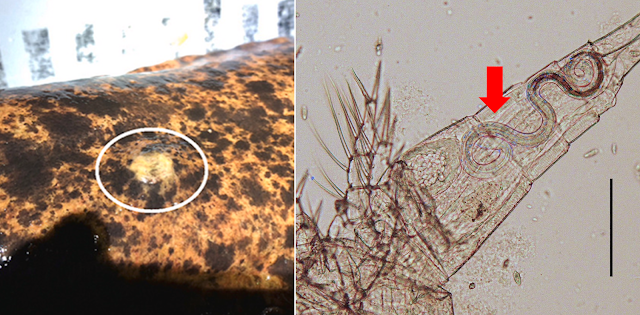

As mentioned at the start of this post, hairworms found in the outside world parasitise a wide range of arthropods, but since G. wulingensis is found only in caves, its host choice is more limited. Given crickets are common hosts for hairworms aboveground, a cave-dwelling cricket would be the ideal hosts for G. wulingensis. In this case, the unlucky chosen one happens to be a species of camel cricket.

Compared with the house or field crickets that most people are more familiar with, camel crickets look rather gangly, with their long slender legs and antennae. They are often called cave crickets because of their tendency to live in caves, along with similar human-made structures such as abandoned mines, sewers and wells. But this cave-dwelling habit also brings them in contact with G. wulingensis, which turns these leggy crickets into living incubators.

Currently, only the adult stages of G. wulingensis have been found, and while the rest of the life cycle is presently unknown, it is probably similar to that of other hairworms - with the larval stage in small invertebrates, and the adult worm developing in and emerging from larger arthropods. While most hairworms are brown in colour, G. wulingensis is entirely white and when shined under light, it gives off a rainbow iridescence. It might be tempting to think that this might have something to do with its lightless habitat, there are other hairworms living aboveground which also have pale complexions.

The emergence of hairworms from their hosts usually follow a seasonal pattern, but seasons don't really mean as much when you're living in a dark cave, and researchers found adult G. wulingensis all year round in the caves, with worms in puddles, soil, and sometimes even crawling up the cave walls. These adult hairworms can live for up to 3 months, which gives them plenty of time to find a mate and produce the next generation.

Caves and other subterranean environments are largely unexplored, and the fauna living in those caves constitute a part of Earth's hidden biodiversity that remains unaccounted for. But the parasites that infect those cave-dwellers presents an even deeper layer of hidden biodiversity, which goes to show that in biology, you can always go deeper

Reference:

.png)