At the top of this blog, there is a quote by Jonathan Swift about how fleas have smaller fleas that bite them. Indeed, parasites becoming host to other types of parasites is actually a rather common phenomenon in the natural world. Those who would parasitise the parasites are called "hyperparasites".

|

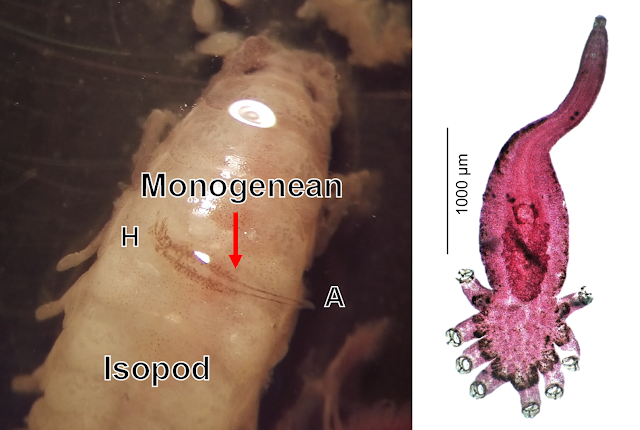

| Left: Cyclocotyla bellones on the back of a Ceratothoa isopod, Right: C. bellones coloured red with Carmine staining. Photos from Figure 1 and 5 of the paper. |

The parasite featured in this post was once suspected of being a hyperparasite. Cyclocotyla bellones is a species of monogenean - it belongs to a diverse group of parasitic flatworms that mostly live on the body of fish, parasitising the fins, skins, and gills of their hosts. But unlike other monogeneans, C. bellones does not attach itself to any part of a fish's body, instead it prefers to stick its suckers onto the carapace of parasitic isopods, such Ceratothoa - the infamous tongue biter. Since Ceratothoa is itself a fish parasite, and C. bellones is routinely found attached to those tongue-biters, this has led some to think that it might be a hyperparasite of those parasitic crustaceans.

But it takes more than simply sticking yourself onto another organism to be considered as a parasite of it. After all, there are algae that grow on the body of various aquatic creatures, or barnacles that are found on the backs of large marine animals like whales and turtles. But those are not considered as parasites as they don't treat their host as a food source, merely as a sturdy surface they can cling to - they're known as epibionts.

So strictly speaking, for Cyclocotyla to be a parasite of the isopod, it needs to be feeding on or obtaining its nutrient directly from its isopod mount. When scientists examine the bodies of the tongue-biters with C. bellones on them, they seem to be pretty unscathed. There aren't any scratches or holes on the isopod's body which you'd expect if C. bellones had been feeding on it. Indeed, the monogenean's mouthpart seems ill-suited for scraping through the isopod's carapace.

Additionally, C. bellones' gut is filled with some kind of dark substance similar to those found in other, related monogenean species. This is most likely digested blood from the fish, which the monogenean has either sucked directly from the fish's gills, or indirectly via the feeding action of its isopod mount. Let's not forget that the isopod itself is a fish parasite that feeds on its host's blood, so if it gets a bit messy during mealtime, perhaps Cyclocotyla is there to suck up any spilled blood. Or it might be doing a bit of both.

The researcher noted that Cyclocotyla is not alone in its habit of riding isopods. Other monogeneans in its family (Diclidophoridae) have also been recorded as attaching to parasitic isopods of fish. And aside from riding isopods, they all share one thing in common - a long, stretchy forebody, looking somewhat like the neck of sauropod dinosaurs. Much like how the neck of those dinosaurs allowed them to browse vegetation from a wide area, the long forebody of Cyclocotyla allows it to graze on the fish's gills while sitting high on the back of an isopod. So fish blood is what C. bellone is really after - the isopod is merely a convenient platform for it to sit on.

But why should these monogeneans even ride on an isopod in the first place? Cyclocotyla and others like it have perfectly good sets of suckers for clinging to a fish's gills. Indeed, there are other similarly-equipped monogeneans that live just fine as fish ectoparasites without doing so from the back of an isopod. Well, that's because the fish themselves don't take too kindly to the monogeneans' presence. These flatworms are constantly under attack from the fish's immune system, which bombards them with all kinds of enzymes, antibodies, and immune cells. By avoiding direct contact with the fish's tissue, Cyclocotyla and other isopod-riders can avoid being ravaged by the host's immune system - which is something that other monogeneans have to deal with on a constant basis.

So it seems that Cyclocotyla and other isopod-riding monogeneans are no hyperparasites - they're all just regular fish parasites that happen to prefer doing so while sitting on the backs of isopods. Cyclocotyla bellones prefers to share in the feast of fish blood with its isopod mount, while sitting high above the wrath of the host's immune response.

Reference:

No comments:

Post a Comment