Dracunculidae is a family of worms with a nasty reputation. Most of this is due to Dracunculus medinensis, also known as the Guinea Worm which causes its human hosts such painful suffering that the World Health Organisation has set out to eradicate it. As of now, Guinea Worm has mostly been eliminated from the human population, though it persists in dogs. But there are also many other species of dracunculid worms out there, infecting various animals including other mammals, as well as reptiles. In fact the majority of known dracunculid worms are parasites of snakes.

|

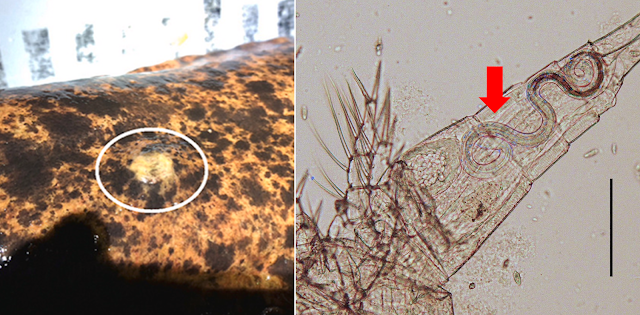

| Left: Lesion caused by Kamegainema cingula on the skin of a Japanese Giant Salamander (from graphical abstract of the paper). Right: Larval K. cingula (indicated by the red arrow) in a copepod (from Fig. 4 of this paper) |

Most species in the Dracunculidae family are in the Dracunculus genus, but Kamegainema cingula is one which stands out from the crowd. Aside from belonging to its own distinct genus, it also lives in a very distinct host - the Japanese Giant Salamander. Usually, K. cingula dwells underneath the salamander's skin, hidden out of sight. But when it comes time for the parasite to release its larvae, it produces a lesion on the salamander's skin from which it unloads its offspring.

Researchers in Japan studying these parasites examined salamanders from rivers systems in the Hyōgo and Kyoto prefectures. They did so by walking through the streams at night, examining the salamanders they came across for skin lesions associated with K. cingula, and extracting the parasite whenever it was possible to do so without injuring the salamander. The worms were only visible during April to June, between spring and early summer, when they would poke out of those skin lesions to release their larvae.

Like the infamous Guinea Worm, the larval K. cingula uses tiny copepods as its intermediate host - which scientists have previously confirmed via experimental infection. From there, it is possible that the juvenile worms might infect fish as paratenic (transport) hosts first before reaching the salamander, since adult giant salamanders won't usually eat speck-size copepods, but they would definitely eat a fish.

Genetic analyses of those worms revealed that evolutionary speaking, Kamegainema occupies a key position in the Guinea worm family tree, having split off early during its evolution from the Guinea worms and the rest of its relatives. In a way, K. cingula and its life cycle could possibly represent the ancestral condition for dracunculid worms, where the parasite is able to release its larvae freely into the surrounding waters whenever it wants.

There are two other families of roundworms which are related to the dracunculids - Micropleuridae which includes worms that infect crocodiles, turtles, and sharks, and the Philometridae, a family of fish parasites that squeezes themselves into awkward places in a fish's body including their muscles and gonads. It is notable that all those worms mostly infect aquatic hosts or at least animals that spend extended periods of time in the water. In this way, by infecting an amphibian, Kamegainema is sort of at an evolutionary crossroad between worms like the fish-dwelling philometrids and those that infect land-dwelling animals like the Guinea worm.

So the ancestor of the Guinea worm might have started out infecting aquatic animals, but when the dracunculid worms started infecting land-dwellers, it needed some drastic adaptations to ensure that it can still reach the water to complete its life cycle. And that adaptation ended up being the ability to coax their hosts into the water by inflicting fiery pain upon them.

The idea that a successful parasite is one that lives in harmony with its host and inflicts minimal harm has no basis in nature - sometimes, the solution to completing a life cycle includes causing the host agony and suffering.

Reference:

No comments:

Post a Comment